Affiliate links may be included for your convenience. View our privacy and affiliates policy for details.

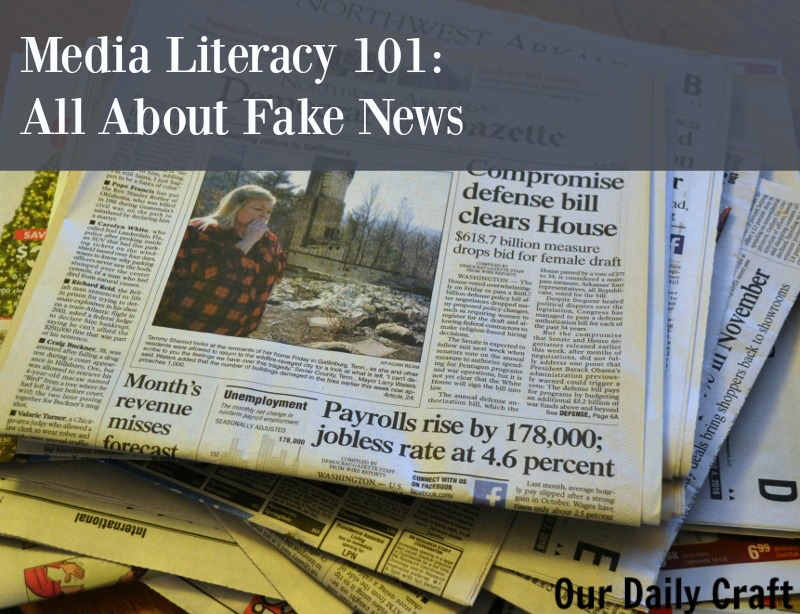

Continuing my media literacy 101 series today, I wanted to talk about fake news, what it is, how to recognize it and what to do about it.

What is Fake News?

Contrary to what our President-elect might have you believe, fake news is not news you don’t agree with, or opinions that are not your own. It’s not things you wish weren’t true or things you want to go away so you label them as fake in the hope people will stop paying attention.

Fake news comes from websites that are either highly partisan in nature or made to look like legitimate news sources (sometimes both) that actually make up stories. Sometimes there’s a kernel of truth that’s blown out of proportion; other times it’s just completely false.

Remember that child sex ring that was supposedly being run out of a pizza place by Hillary Clinton? I mean, it sounds fake, right? (It is.) But at least one guy with guns thought it was real and drove six hours to investigate, firing a weapon before being arrested.

Why is Fake News Such a Big Problem?

It only takes one person with guns believing something ridiculous is true and acting on that information to cause real harm for the rest of us.

But even when people don’t take that kind of action based on fake news, it might cause them to believe untrue things about people. Certainly more than one person read those fake stories and thought Hillary really was hiding kids in the back of a pizza joint.

And while we’ll never know if fake news changed the outcome of the election, it was certainly a factor. In other countries it has been a factor in the past, and at least one fake news writer has taken the blame for Trump being elected. (Another doesn’t, and has no regrets about highlighting the crazy things that right-wing people will believe.)

And while Mark Zuckerberg says it’s not Facebook’s fault, such stories would not spread as quickly or as far without the ability to share them on social media.

And with nearly half of all adults saying they get news from Facebook, and 88 percent of millennials reporting they regularly get news from Facebook, it’s hard not to see social networks as part of the problem. (Another study found fake news was just as likely to be shared as stories with true information in them.)

While you might think younger people are more savvy on social media than people who didn’t grow up with it, a recent study from Stanford found kids from middle school through college were taken in by fake news with a “stunning and dismaying consistency,” according to researchers.

- More than 80 percent of middle schoolers in the survey couldn’t tell a native ad (ie., sponsored content) from regular editorial, and more than 80 percent of high school students accepted fake photos without sourcing as fact.

- Just a quarter of high school students could explain what the blue checkmark (denoting a verified account) meant on Facebook, and 30 percent found the fake source of news more trustworthy than the real one.

- Most college students didn’t note the potential bias in a tweet from MoveOn.org, and more than half evaluated the trustworthiness of the information without even clicking on the link. Clearly the need for media literacy and proper evaluation of sources is vital for all age groups.

What Can We Do About Fake News?

The main thing consumers of news can do to stop fake news is to recognize it, refuse to share it, call people out when they share it and block those sites on social media.

There are a lot of steps involved in sussing out fake news, but this article from CNN is excellent. It lays out the different varieties of fake and misleading news and how to figure out what’s fake. Most commonly: strange URLs that are close to legitimate sources, or sound like they might be legitimate sources, but really aren’t.

Check out the International Fact-Checkers Network, and know that if one of the signatories is reporting a story as false, they have done the legwork to prove it (Snopes, Factcheck.org and the Washington Post Fact Checker are all on the list, by the way).

Other good places for learning about bias and media literacy are the News Literacy Project and the Center for News Literacy. Like them on Facebook or Twitter, share their stories and educate yourself so you can be a more informed consumer of news.

What would you add? I’d love to hear your thoughts.